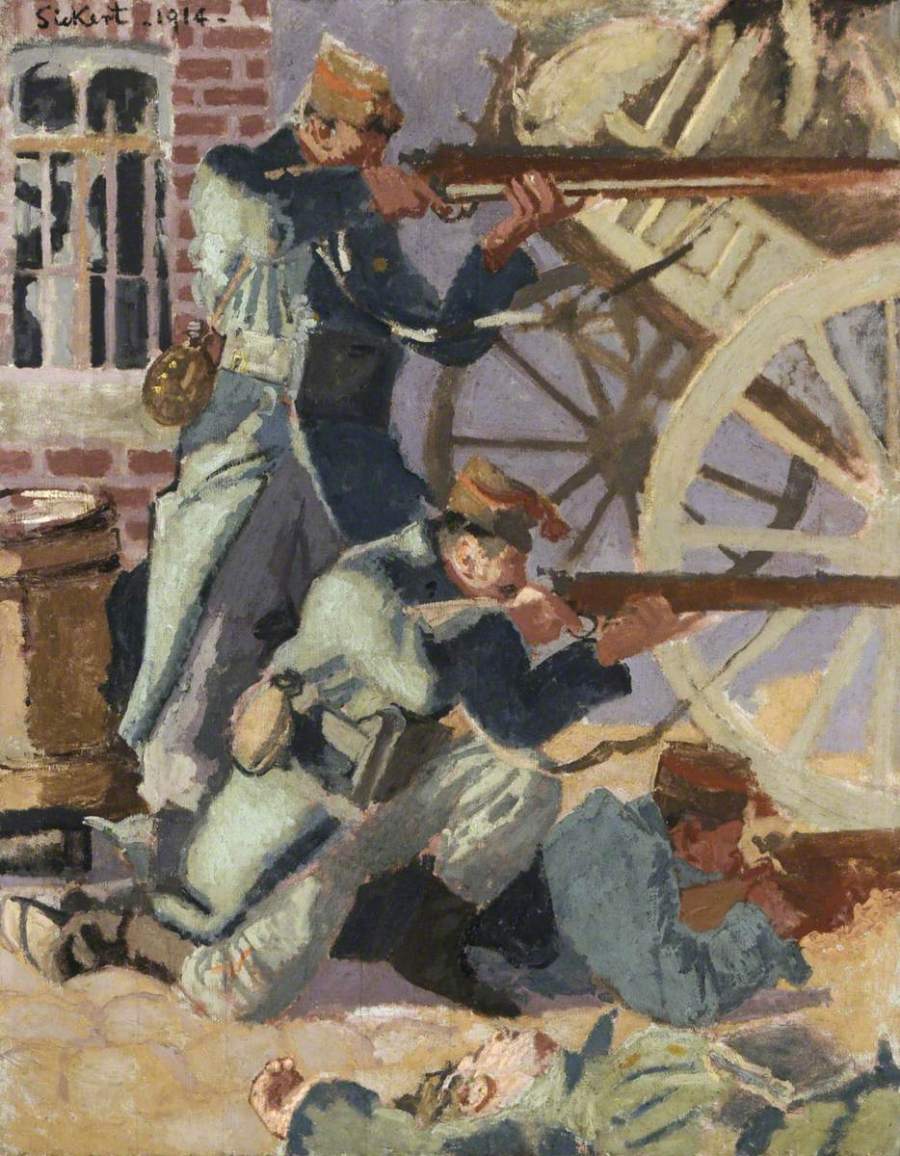

[Notes from “Art and World War I” discussion at The Beecroft Gallery, @Southend Museums, May 2017]

The anniversary of the 1914-1918 war has been recognised with numerous books, exhibitions and artworks as we remember the millions of people killed, the millions more caught up in the first ‘modern’ war; the all-encompassing horror that reached across the world.

Whilst in 1914 young men were taking up the call to arms with patriotic vigour and adventurous enthusiasm, it wasn’t all over by Christmas and the year 1915 saw untold slaughter. Men with horrendous injuries – physical and mental – were coming into the hospitals with fearful stories: experiences that seemed incompatible with the “all to victory” slogans of the newspapers. In visual culture similarly, the war images were primarily “inspirational” portraits of the King and military leaders in uniform, or the call-to-arms posters pasted on every other lamp-post.

“The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our lifetime” declared British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey – culture, even civilization itself, appeared to be at an end. The avant-garde artists of Europe, may of whom had been active in the brilliant cauldron of creativity that was Paris, were now forced to leave their easels and return to their home nations, many signing up of course to military service. “Rent or furled are all Art’s ensigns” wrote Wilfred Own in his poem “1914”.

It wasn’t until 1916 that a growing recognition of the importance of visual art inspired the formation of an official enterprise. Initially under the remit of the propaganda department at Wellington House, then incorporated into the Ministry of Information; the War Artists scheme would lead to exhibitions both across Britain and abroad; magazine publications such as “The Western Front” and “British Artists at the Front” and ultimately the creation of the Imperial War Museum.

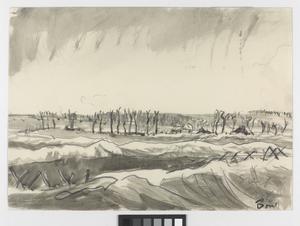

One of the first to go out to Europe in the capacity of Official War Artist was Muirhead Bone who went to France in 1916 with a commission to make appropriate drawings for both propaganda and the historical record.

Two drawings from the Imperial War Museum collection stand out to me [click the links for larger size]

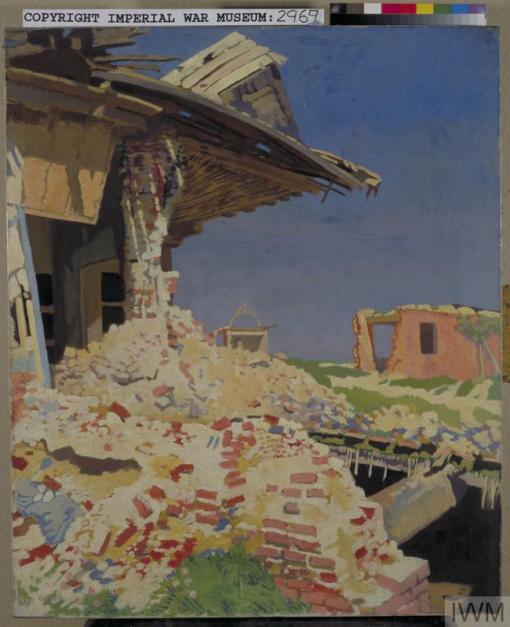

Fricourt Village : After the Capture by the British

The ‘before’ and ‘after’ are shocking contrasts – and they revealed a truth, a reality, previously unavailable to the British public.

[There is a resume of Bone’s war career at https://history.blog.gov.uk/2014/07/22/sir-muirhead-bone-first-official-war-artist/ and many more images can be seen at the Imperial War Museum website: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?query=muirhead+bone&=Search%5D

It had been recognised that art was not only valuable as propaganda and reportage, but also as document and most importantly as answering the public’s call for truth – people wanted to see, to understand, what the men on the frontlines were going through. The turning point may well have been an exhibition of CRW Nevinson’s paintings.

Nevinson had been at the forefront of the British avant-garde as a member of the Vorticist group [http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/v/vorticism]; flagrantly displaying a dynamic, aggressive futurist style in his paintings. With the start of war, and unable to enlist with the army for health reasons, he volunteered for the Red Cross, serving as ambulance driver, stretcher bearer and interpreter. The horror of the medical situation just behind the frontlines was shocking; Nevinson describes the hospital quarters “a shed full of dead, wounded and dying”. Invalided home in early 1915, he realised the huge disparity between what he had seen and what the general public imagined: “Back I went to London, to see life still unshaken, with bands playing, drums banging, the armies marching and the newspapers telling us nothing at all” [quoted in Richard Cork’s “A Biter Truth”]. Recovered from his own injuries and working at a London hospital, Nevinson started painting. The Daily News reporters had been calling for a new patriotic art that documented the campaigns, imagining masterpieces with the theme: victory. They did not expect the explicit, full-frontal nerve shattering art that Nevinson would show the world:

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1989-1946) Bursting Shell [1915; Tate; @Tate @TateImages]

Whilst Bursting Shell combines fragmentation, abstraction and blinding colour to disorientate the viewer, Nevinson also represents the brutal reality of his experiences:

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1989-1946) La Patrie [1916; Birmingham Museums @BM_AG; image c/o artuk.org @artukdotorg ]

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1989-1946) La Patrie [1916; Birmingham Museums @BM_AG; image c/o artuk.org @artukdotorg ]

There is nowhere to turn from the agony and torment of these men lying bandaged on makeshift wooden boards as yet more stretcher-bearers arrive with more wounded men. There is no sentiment here, no patriotism or idealist heroism – just the brutal reality that now has to be faced. And one aspect of this brutal reality was the industrial modernity of the weapons.

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1989-1946) La Mitrailleuse [1915; Tate; @Tate]

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1989-1946) La Mitrailleuse [1915; Tate; @Tate]

Nevinson’s representation of the machine gunners is intense; dug-in; claustrophobic as sharp jagged struts and barbed wire enclose them. The men are no longer fleshly human individuals but at one with the gun, cogs in the war-machine as they concentrate at their posts – whilst a dead comrade lies at their feet in the trench.

Whilst many critics had smarted at avant-garde art, it was becoming apparent that modern war had to be represented by modern means; moreover, it was these young men – trained as artists and knowledgeable of Post-Impressionsim, Cubism and Futurism – that were out there fighting, experiencing the trenches, the battles and the carnage.

For those who became Official War Artists, there was no advice given from above – both subject matter and style of painting were left entirely to the artists themselves. And it is perhaps the drawings and sketches made at the front that bring us closest to what these artists experienced, what they were seeing 100 years ago.

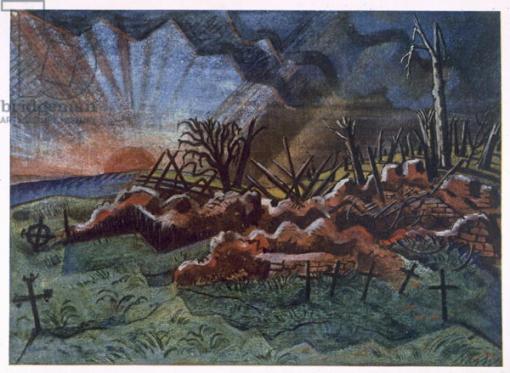

Paul Nash had been in the trenches with the Artists Rifles Brigade from February to May 1917; he returned in October as an Official War Artist; his sketches focus the shattered landscape which comes to symbolise the destruction and carnage of all-out-war.

Paul Nash (1889-1946) The Field of Passchendaele [1917; Manchester Art Galleries; @mcrartgallery; image c/o @BridgemanImages]

Paul Nash (1889-1946) Sunrise, Ruins of a Hospice, north west of Wytschaete, destroyed by bombardment [1917; private collection c/o @BridgemanImages]

Paul Nash (1889-1946) A Farm, Wytschaete, Belgium [1917; private collection c/o @BridgemanImages]

“I have seen the most frightful nightmare of a country… unspeakable, utterly undescribable… no glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere. Sunset and sunrise are blasphemous… The rain drives on, the stinking mud… the black trees ooze and sweat… I am no longer an artist interested and curious. I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men… inarticulate will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth.”

[This was written by Paul Nash on 16th November 1917 to his wife Margaret, quoted in David Boyd Haycock’s book “A Crisis of Brilliance”]

As Paul Nash focused on a terrible landscape of mud, water, blasted trees in the dun colours of gloom or in acidic crayon, Eric Kennington turned to portrait sketches. Far from the authority figures photographed for the press at the start of the war, the ‘ordinary’ Tommy was increasingly important not as the abstract ‘machine cog’ (as in Nevinson’s paintings) but as an individual.

Eric Kennington (1888-1960) Back to Billets [1917; Imperial War Museum @I_W_M]

Like Kennington, William Orpen was out in France for most of 1917 completing an enormous portfolio of works, now in the Imperial War Museum [http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?query=william+orpen+1917&=Search], showing scenes from soldier’s activities to shattered buildings. Perhaps most harrowing are his depictions of the physical and psychological damage of war.

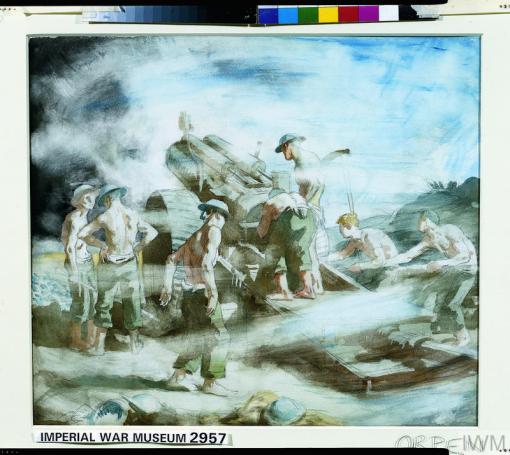

William Orpen (1878-1931) A Howitzer in Action [1917; Imperial War Museum @I_W_M]

William Orpen (1878-1931) The Main Street, Combles [1917; Imperial War Museum]

William Orpen (1878-1931) The Receiving Room – The 42nd Stationary Hospital [1917; Imperial War Museum @I_W_M]

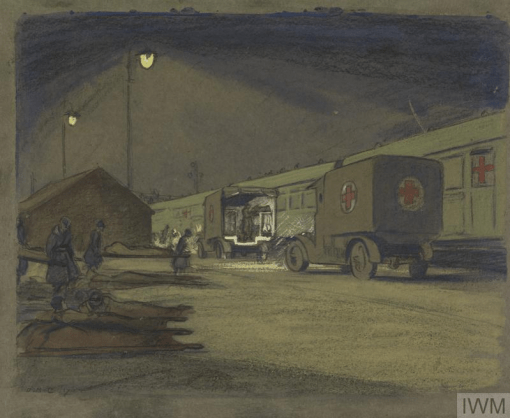

Whilst women artists were not permitted to go to the front, many were working just behind the front lines having volunteered for the medical corps. such as Olive Mudie-Cooke whose watercoloured drawings reveal not only everyday activities but the care taken by nurses over the wounded soldiers.

Olive Mudie-Cooke (1890-1925) Etaples Hospital Siding : a VAD convoy unloading an ambulance train at night [1917; Imperial War Museum]

Olive Mudie-Cooke (1890-1925) In an Ambulance : a VAD lighting a cigarette for a patient [c.1918; IWM]

These artists were bringing their scenes of experience to viewers at home hungry for knowledge. Mind, the Home Front, as crucial to the war effort as the frontline in many ways, also saw dramatic changes and new experiences. These again were recognised by the official war commission – and I’ll return to these in a separate posting – as they are key to the recognition of women as factory workers, farm-works and, indeed, artists.

One other aspect of art from World War I also worth recognising is that of aerial perspectives. The use of aircraft in war was again new and, as artists were increasingly commissioned from across the forces, so brothers Sydney and Richard Carline – pilots in the Royal Flying Corps – became Official War Artists in 1918. Their sketches (and eventual paintings) would show unique views of the landscape in Europe and beyond, as they take us – the viewer – aloft with them.

Richard Carline (1896–1980) Ypres Seen from an Aeroplane [1918; IWM]

Sydney William Carline (1888–1929) A British Pilot in a BE2c Approaching Hit along the Course of the River Euphrates, July 1919 [1919; IWM]

Again, there’s much more at http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/search?query=Carline+1918&=Search

Recommended books:

The Imperial War Museum’s “Art From the First World War” is of course a brilliant introductory overview of key works.

David Boyd Haycock’s excellent “A Crisis of Brilliance” tells the story of the Slade generation caught up in the war, and for a more fictional account try Pat Barker’s brilliant trilogy “Regeneration”.