Category Archives: Uncategorized

Posted in Uncategorized

Permalink Enter your password to view comments.

Posted in Uncategorized

Permalink Enter your password to view comments.

Posted in Uncategorized

Permalink Enter your password to view comments.

Posted in Uncategorized

Permalink Enter your password to view comments.

The Romantics Return: William Blake on the BBC

So absolutely glorious to hear the two versions of “Jerusalem” at the Proms last evening – not only Hubert Parry’s traditional version, but Errolyn Warren’s delicious re-visioning “Jerusalem – our clouded hills” in which she

has added a blues feeling and African rhythm.

Subtitled ‘our clouded hills’, her piece is dedicated to the Windrush generation and encourages a communion of Commonwealth nations…

(the BBC Last Night of the Proms 2020 is available on i-player for the next month).

It made me turn to the Blake Archive to look up Blake’s designs for Jerusalem created between 1804-1820, including this dramatic title page:

Jerusalem – The Emanation of the Giant Albion (Yale Centre for British Art).

With more detail on the website, the Tate summarises the complex poem:

In Jerusalem, Albion (England) is infected with a ‘soul disease’ and her ‘mountains run with blood’ as a consequence of the Napoleonic wars. Religion exists only to help monarchy and clergy exploit the lower classes. Greed and war have obscured the true message of religion. However, if Albion can be reunited with Jerusalem, the story goes, then all humanity will once again be bound together with love.

*

And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon Englands mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On Englands pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

Intriguingly, “Jerusalem” – the song we all know, with its music written by Hubert Parry and its orchestration by Edward Elgar – is actually from Blake’s poem “Milton” in which he recalls the possibility that Jesus had once travelled to England (Glastonbury) with Joseph of Arimathea.

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

If so, and the dark satanic mills of Blake’s contemporary world – with its Enlightenment science and industrial rationalism – were obscuring the spiritual knowledge and perceptive vision that Heaven was once here, then

Bring me my Bow of burning gold:

Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold:

Bring me my Chariot of Fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In Englands green & pleasant Land.

*

It’s that ‘Mental Fight’ that is so important here – the power of art, poetry, the creative imagination – and takes us to Simon Schama’s new series The Romantics and Us in which (in part one, “Passions of the People”) William Blake also makes a significant appearance as “one of the founding fathers of Romanticism”.

Living in a “city growing fat with the profits of Empire” where everyday he saw the extremes of wealth and destitution, Blake was, in Schama’s (really quite emotional tone) “always reaching for that bit of Heaven as he sees everybody as potentially wonderful. That’s his adorable thing… that’s how he sees the world even in the middle of… filthy, cruel, ferocious meat-grinder London.”

I’d highly recommend watching it as Testament brings home the relevance of Blake today and Simon Schama marks the passions of William Blake, Eugene Gericault, Mary Wollstonecraft and others and the impact they’ve had on our subsequent histories.

*

Have we, in 2020, entered a new Romantic Age?

Orc – a vigorous youth, surrounded by the fires of revolutionary passion – symbolises the spirit of rebellion and the love of freedom [Tate].

***

Posted in Uncategorized

Posted in Uncategorized

Permalink Enter your password to view comments.

Posted in Uncategorized

Permalink Enter your password to view comments.

Picture Postcard: Two extraordinary Elizabethan Portraits

I’ve just watched James Fox’s “A Very British Renaissance: The Elizabethan Code” on BBC i-player (available for the next few weeks) and he highlighted two extraordinary paintings from the Elizabethan Age, well worth watching (from about 14minutes in).

The first stretches the concept of what a portrait might be:

It’s a “portrait” of Sir Henry Unton, commissioned by his widow in about 1596 and at the National Portrait Gallery. Unfortunately the artist is unknown, but the painting shows scenes from Upton’s life – from birth in the lower right hand corner to his death.

I find it quite amazing – indeed rather exciting! It seems to recall medieval church wall-painting rather than suggesting the ‘face’ portraits that would come to dominate British art.

The second rather fabulous painting James Fox discusses is again a portrait which currently resides in the archives of Northampton Art Gallery:

Sir Christopher Hatton, by an unknown artist again (although the artist has pictured himself at the bottom left).

In turn the painting includes all sorts of symbolism to decode – and what brilliant colours! – but to fully appreciate the whole it also needs to be turned about as the imagery continues onto the back.

There are some notes about the work online at artuk.org – including the possibility that the artist was from the studio of portrait painter William Segar (1554-1633) and even that an astrologer (depicted at the bottom right?) may have been involved in the painting.

Otherwise there seems to be very little information, so it’s fascinating to see the programme.

And how very intriguing these pictures are, so very “eccentric” – showing, as Fox says, that English Renaissance painting was experimental, rich and sophisticated.

***

Posted in Uncategorized

Toulouse-Lautrec & The Englishmen at the Moulin Rouge

In 1892, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec painted “The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge”, now in The Metropolitan Museum, New York. The Englishman in question is William Tom Warrener (1861-1934) who had become friends with Lautrec in the early 1890s.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901) The Englishman at the Moulin Rouge [1892, Metropolitan Museum, New York]

Patrick O’Connor (1) suggests there is a sly irony to the scene: the Englishman is mischievously characterised with a certain embarrassed reserve – note his reddening ear – as he enters into conversation with the two ladies of the Moulin Rouge (2). That the working title for the piece was “Flirt” (3) also suggests the perhaps risqué nature of their talk. Nevertheless, the painting would serve as the basis for a poster of the same name (Musee Toulouse-Lautrec), the man now reduced to a near shadow (to represent Englishmen in general, rather than portraying Warrener in particular). However, Warrener does then turn up again in another of Lautrec’s 1892 paintings: “Jane Avril Dancing”, now in the Musee d’Orsay (4) – he is at the back of the scene with an unidentified woman.

So, who was William Tom Warrener? And what was he doing in Paris in the early 1890s?

Well there is sadly rather little information on him (5), especially at this time in his life. Julia Frey writes that he was “a painter from an influential English family, who had moved to Paris in the mid-1880s to study at the Academie Julian. He moved to Montmartre in the 1890s where he met Henri [Toulouse-Lautrec]” (p.314). And, in fact, he showed work at the Paris Salon, not returning to his hometown of Lincoln until 1906 where, whilst taking up his role in the family (coal) business, he also set up the Lincolnshire Drawing Society and would, later, become President of the Lincolnshire Artists’ Society. A number of his paintings and sketchbooks (6) are now held by the Usher Gallery in Lincoln, examples of which can be seen on the artuk.org website revealing that whilst in France he worked at the artists’ colony Grez-sur-Loing and explored the bright sunlit colours of Impressionism.

However, there are also two paintings that come from his adventures in Montmartre with Toulouse-Lautrec: “Quadrille I” and “Quadrille II” (both dated circa 1890 and both in the Usher Gallery collection).

Later in her biography of Toulouse-Lautrec, Julia Frey notes: “In the late 1880s and early 1890s, he befriended a number of younger English artists in Paris” (p.384). These included William Rothenstein who, in 1931, would write up his recollections of the time he spent in Paris as a young art student (7), recognising both the thrill and the folly of bohemian life as he moved from the Left Bank “all very well for poets and scholars” to Montmartre “essentially the artists’ quarter” – he was just seventeen years old.

“Puvis de Chavannes had a studio on the Place Pigalle, while Alfred Stevens lived close by, and in the Rue Victor Masse lived Degas. At Montmartre also were the Nouvelles Athenes and the Pere Lathuille, [cafes] where Manet, Zola, Pissarro and Monet, indeed, all the original Impressionists used to meet. The temptation, therefore, to cross the river and live on the heights was too strong to resist” (p.56).

It was at a restaurant in Place Pigalle that he used to meet with friends for lunch:

“The Rat Mort by night had a somewhat doubtful reputation, but during the day was frequented by painters and poets. As a matter of fact it was a notorious centre of lesbianism… [and] it was here that I first met Toulouse-Lautrec…” (p.59).

Then there was, of course, the Moulin Rouge:

“[A]n open air café-concert where one could watch people sitting and walking under coloured lamps and under the stars. Inside the great dancing hall, its walls covered with mirrors… was the dancing of the cancan. …In most places dancers performed on a stage; at the Moulin they mixed with the crowd… suddenly the band would strike up, and they formed a set in the middle of the floor, while a crowd gathered closely around them. It was a strange dance; a sort of quadrille, with [the men] twisting their legs into uncouth shapes… their partners [with] one leg on the ground, the other raised almost vertically, previous to the sudden descent – le grand ecart” (p.62).

Another student artist in their group was Charles Conder who, one evening – “having drunk more than was good for us” – suggested they paint the Moulin Rouge dancers “there and then”. Whilst I haven’t traced the “wild results” of Rothenstein’s painting-spree, the Manchester Art Gallery has Conder’s “The Moulin Rouge” (1890) which may well have been painted that drunken night.

Indeed the script at the bottom-right of the painting reads:

“CHAS. CONDER. TO. CHAS. ROTHENSTIEN (sic) / IN MEMORY. Of. A. PLEASANT EVENING. / 30.OCT.1890.” (8)

“Can anyone wonder that [we] were fascinated by this strange and vivid life?” (p.62), asks Rothenstein – indeed, it must have been an extraordinary time for these young artists there with the ‘in-crowd’ of bohemian Montmartre.

***

Please note: this is just the beginning of a longer research piece on British artists in late 19th-century France. Any further resources or references you may have would be greatly appreciated. Please contact via Twitter @TheCommonViewer.

***

(1) Patrick O’Connor: “Toulouse-Lautrec: The Nightlife of Paris” (Phaidon, 1991, p.32)

(2) The women have been identified as Rayon d’Or and La Sauterelle: http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437835; although biographer Julia Frey suggests they might be La Goulue and La Mome Fromage

(3) Julia Frey: Toulouse-Lautrec – A Life (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1994, p.314)

(4) https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/collections/works-in-focus/painting/commentaire_id/jane-avril-dancing-8969.html?cHash=8fc9922fcb

(5) See Wikipedia for a brief biographical overview: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_T._Warrener

(6) The sketchbooks in the The Usher Archives are undated and not digitised. I must say a huge thank you to the Collections Development Officer at Lincoln County Council, Dawn Heywood for the kind help and information she has found.

(7) William Rothenstein: “Men and memories: Recollections of William Rothenstein 1871-1900” (Faber & Faber, 1931) (8) Many thanks to Manchester Art Gallery for this information. (9) There’s an extraordinary – indeed surrealist – picture by Charles Conder at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge called “A Dream in Absinthe” from 1890 (see http://webapps.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/explorer/index.php?qu=Charles%20Conder%20Absinthe&oid=14761)

Posted in Uncategorized

Review: The 58th Essex Open exhibition at The Beecroft Art Gallery

There is a thrill and a challenge in viewing the current Essex Open exhibition.

The thrill is that of variety, for there is no single subject theme or painting style taken up by the artists of Essex; nor – although the exhibition consists primarily of oil paintings – one medium, for there are watercolours, prints, photographs and sculptures. The challenge, then, is for the viewer: how to take on board the diversity before us as each artefact demands we look at it differently to the previous one. By the time we have reach the end of such an extensive show – divided across two floors of The Beecroft Gallery – we are exhausted, having worked our way through so many ways of seeing and responses. Looking back at the experience, certain elements rise to the surface of course; but, truly, one should return to look again and again.

(nb: images were photographed by me and are only details of the complete artworks)

“Sunlit Dinghies” by Anita Pickles & “View from Chester Wall” by Malcolm Perry

So how should we approach this exhibition? Perhaps that geographical “Essex” might be the key, for certainly many of the pictures reflect local life and everyday scenes. “Sunlit Dinghies” by Anita Pickles is an image we all recognise immediately: it could be anywhere along the coast of Essex, the tide out, the scene a snapshot as we walk along the beach on a sunny afternoon; the scent of sea air palpable. Come into town, and Malcolm Perry’s “View from Chester Wall” is again so recognisable and, despite presenting a particular place, stands for so many of our towns and streets: the bustle of Saturday afternoon shopping; the architecture of historical Essex. As with Pickles’ work, it is a view that captures both an immediately present-day scene, yet one that has been this way forever, and so stirring personal and shared memories.

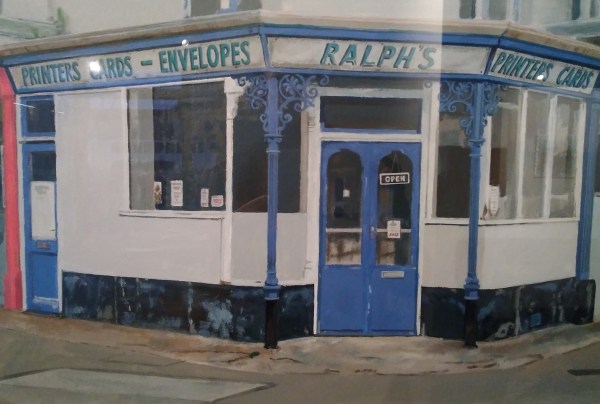

“Ralph’s – Corner of Park and Hamlet” by Stephen Gibbs

And I couldn’t resist “Ralph’s – Corner of Park and Hamlet” by Stephen Gibbs. Again it brilliantly captures an immediately recognisable scene, a somewhat dilapidated shop on a street corner that we probably pass every single day never thinking it should be elevated to ‘art’. It resonates with familiarity, as if it couldn’t be of anywhere else but Westcliff; and it stands for something – all those independent shops and businesses that cluster around Hamlet Court Road, ramshackle yes, barely surviving probably, yet remaining stubbornly “open”.

“Turbulent Sky over Fen Bridge” by Paul Franks & “Picardy Flowers” by Liz Hine

Whilst Gibbs’s picture can be framed within a ‘local’ ‘Essex’ theme, we might also recognise it within the broader contexts of art history – paintings of shopfronts by both Whistler and Sickert come to mind. Indeed a number of works in this current exhibition echo other – more famous – artists and pictures. “Turbulent Sky over Fen Bridge” by Paul Franks cannot but recall Constable in those looming, darkening clouds and gorgeously rich colours as the light picks out the bridge among the trees. It is – almost essentially – East Anglian. Then, alongside, is Liz Hine’s “Picardy Flowers” which makes us long for summer, to lie down in a field and gaze up into a blue, blue sky.

“Costa” by Alan Woods

A more playful echoing is “Costa” by Alan Woods which transports Manet’s “A Bar at the Folies-Bergere” to a coffee shop in… Southend High Street? Well, it could be anywhere really. That’s perhaps the irony; the Folies-Bergere being so singularly unique; Costa so ubiquitous. Should we understand this young woman behind the counter as an icon of our times? We bestow a Romantic gaze upon Manet’s painting – imagining the bars of 19th-century Montmartre with a bohemian delight that a Costa coffee-shop could never inspire. Yet the Impressionists sought to portray ‘modern life’ – look at Manet’s barmaid again, for those bars and cafes weren’t such glamorous places at all, indeed they could be rough and threatening – she doesn’t look happy. The refrain on Gibbs’s picture reads “Are you alright my love?” which might be what the barista is asking us, but perhaps it’s what we should be asking her.

“Promenade” by William Barr & “Stand Up” by Adam Smith

A very different sort of play is afoot in William Barr’s “Promenade” as it toys with our senses: how can we look at it in a way that makes sense? Look ‘straight on’ and it seems to be an abstract ‘face’ (is it a dog, even?), the eye reflecting sea and sky; the yellow, then, might refer to a beach. Re-focus and the picture turns into a map, or an aerial view of the shoreline. Perhaps. It is brilliantly defiant. A description that might also encompass some of the sculptures in the exhibition. Adam Smith’s “Stand Up” consists of four standing panels, each collaged with images, colour and graffiti-like painting. Abstract, decorative and mesmerising, it defies categorisation, rejects labelling and refuses any translation into descriptive words: it is, for me, one of the most exciting exhibits on show.

“On-the-Wall Revisited VI” by Steve Whittle

Depictions of local sights and scenes, echoes and allusions to a broader art history, the experience of pure aesthetic sensation… there is one painting that, for me personally, brings each of these elements together: “On-the-Wall Revisited VI” by Steve Whittle. It’s subject is the Chapel of St Peter-on-the-Wall in Bradwell-on-Sea which has been standing against sea and sky for centuries, a place of pilgrimage, peace and spirituality set in contrast to wild nature at the edge of land and sea. Whittle captures the awe of this monumentality within the thrilling drama of art-making itself as we witness the dripping, layering, blending and scratching of colour in his portrayals of grasses and flowers.

So many other paintings should be mentioned, but the exhibition runs until 16th February – and it’s well worth a visit!

Posted in Uncategorized