I’ve been meaning to write a short post about the artist Brett since reading Frances Wilson’s brilliant new biography

Wilson’s discussion of Lawrence’s life is extraordinary in that she weaves in all of his writing (not just the obvious novels) along with his friendships, travels and, let’s face it, his contradictions and eccentricities. Even aside from her subject, however, this is a biography like no other and Wilson’s determinedly creates a narrative – following Dante’s ascent through the circles of Hell – that unfolds in such a way as to portray Lawrence more in his own unique terms, his particular vision and understanding of life, than any straightforward this-happened-then-this-and-then-that. As such it is worth reading as much for an appreciation of the art of biography as for Lawrence’s life story.

Be that as it may, one of the most interesting aspects of Lawrence’s life for me – from the perspective of visual art – is his time in New Mexico. Lawrence had always wanted to set up a community of like-minded souls and when the American socialite and patron of the Taos Art Colony, Mabel Dodge Luhan, invited him, he went, along with his wife Frieda and the artist Brett (he had asked all his other friends to join him, they all said no!).

Brett is hardly known here now, except perhaps among the devotees of all things Bloomsbury. Her ‘full name’ was The Right Honourable Dorothy Eugenie Brett; her dates 1883-1977.

Born into a very well-to-do and actually quite eccentric family, Brett was seen as the most eccentric of them all when she began studying to be an artist at the Slade. It was there – alongside Carrington – that she not only cut off her hair (becoming what Virginia Woolf called “one of the cropheads”) but also cut off most of her names to become, simply, Brett. Despite suffering hearing problems – she used a trumpet she called Toby – she flourished, associating with Augustus John, Katherine Mansfield, the Lawrences, Mark Gertler and, especially during the years of the First World War, Ottoline Morrell at her house in Garsington which became a sanctuary for pacifists and conscientious objectors.

I have to copy & paste Manchester Art Gallery’s description of Brett’s painting “Umbrellas” which goes as follows:

Stylised figure composition in an outdoor park setting. Group of figures in the foreground, comprising bearded man to the right beneath an ivory coloured umbrella, limply holding a book in his right hand. There is a woman in a pale pink dress and yellow hat in the centre beneath a green umbrella, seated in deckchair facing a young man in a grey suit crouching to the left. There are more figures in the background beneath coloured umbrellas to the left and right.

They seem not to be fans of Bloomsbury! The “woman in a pale pink dress” is in fact the great Ottoline Morrell herself, the limp-handed bearded man is Lytton Strachey and the “crouching” young man is Aldous Huxley. The woman leaning on his shoulders is Ottoline’s daughter Julian. Of the “background” figures, the two to the right are Katherine Mansfield and John Middleton Murray, the single figure under the yellow umbrella to the left is Mark Gertler and the person under the blue umbrella is the artist, Brett, herself. The “outdoor setting” is, of course, Garsington Manor.

Painted through the summer of 1917, Brett took Virginia Woolf to see it. Woolf notes in her diary: Brett is a queer imp. She took me to her studio and is evidently very proud of a great picture full of blue umbrellas.

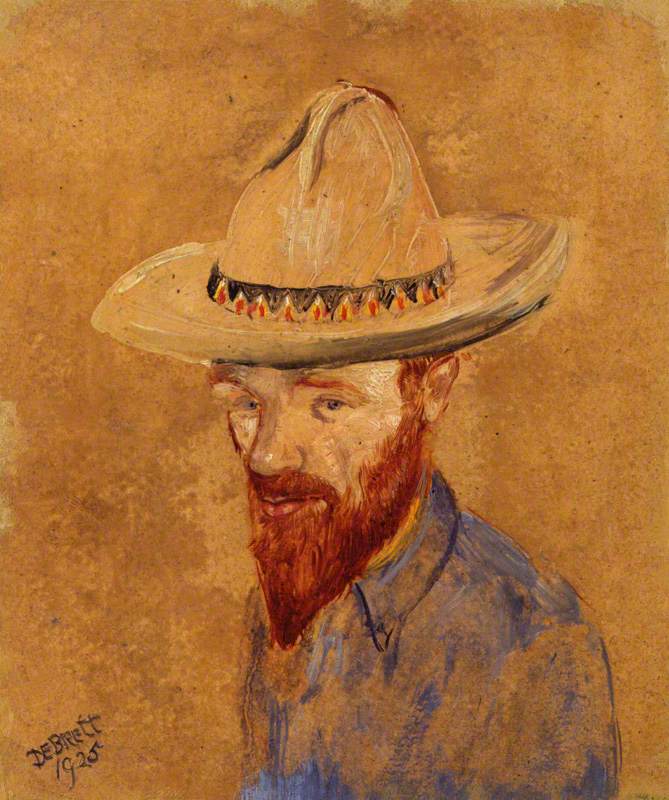

Brett painted Lawrence’s portrait in New Mexico in 1925. The ‘colony’ was an endless drama of comings and goings, but Brett would stay in Taos for the rest of her days. The Sotheby’s website records: [Brett] was immediately enamoured by the new environment, remarking, “I like it better than England. O, for the bigness of it! …Here I’m free from the old conventions …Here I’m truly free” (as quoted in Cassidy, New Mexico Highway Journal, March 1933).

There’s an intriguing Self-Portrait (c/o Addison Rowe Gallery) from this time, 1925, and it looks as if Brett is holding “Toby”, her hearing trumpet:

Many of her paintings took their subjects from the Pueblo Indians’ lives. In Sean Hignett’s biography “Brett – from Bloomsbury to New Mexico” (1984), he recognises how difficult this was, especially for an outsider, alien to the community’s beliefs. However, making friends, Brett soon found a guide to the local religious ceremonies, Trinidad, who was “a discreet mediator and protector in [Brett’s] dealings with the Pueblo”.

It meant that she could attend – though not directly paint, sketch or photograph – the calendar of dances and ceremonies tied to the agricultural seasons and religious feast-days. The only ceremonial painting by Brett in a UK collection is at the Tate, and painted later in 1948:

Tate Catalogue notes:

The artist wrote (17 September 1959) that the dance is almost entirely Spanish in costume, music, etc.: ‘A variation of the old Spanish Folk Dance “Los Christianos y Tor Moros” celebrating the battle which recovered Spain from the Moors in the 15th Century. Brought to Mexico soon after the Conquest, it added “Matinche” (Cortez’ Mistress and Interpreter) as a character, but retained the Spanish El Toro (the bull). It was then brought up into New Mexico where it took on Indian characteristics. [see more on Tate website]

The costumes and masks are fascinating in their detail, the dancers and the two musicians with people looking on from all around; the symmetry and the colours reflect the ritual importance of the dance. It’s quite breath-takingly beautiful.

Hignett writes that the dance often developed “a deep psychic intensity, building up through the long sun-baked day, through hours of non-stop rhythmic shuffling and swaying, low throat-throbbing chanting and the continual rapid pound of drums. The dance grows until quite suddenly it stops and one feels the silence…”

The other extraordinary painting by Brett on the artuk.org website (again at the Tate) is terrifyingly tragic:

Massacre in the Canyon of Death: Vision of the Sun God

The artist wrote (17 September 1959):

‘The Navajo men before leaving for a hunting expedition placed their women and children in a high cave on the side of the towering cliff…. Soon after they left the Spanish soldiers rode through the Canyon. An old woman … jeered and spat, thus giving away their hiding place. The soldiers then climbed up the opposite side of the Canyon and fired into the cave until all the women and children were killed. My painting shows the dying women seeing a vision of the Sun God as they die.’ [Tate website]

The tragedy is there in the red walls of the canyon, the smallness of the figures – but that vision of the Sun God seems to have such strength: at the moment of death the women and children pass beyond earthly life under the Sun God’s gaze. To me, at least, as a cultural outsider, it would seem Brett had a remarkable understanding of local beliefs and was able to convey/translate the meaning and power of them in paint. I wonder about the balance between the documentary aspect, the story-telling and the artistic vision of the paintings. Brett certainly did not paint for foreign/western eyes, indeed it seems many of her paintings were bought by the local community, but one does wonder about their reception and whether the Pueblo Indians recognised themselves, their lives, legends and beliefs in Brett’s imagery.

Of course, through the magic of the digital age, we are also able to “visit” some of the Taos galleries and auction houses to see more of Brett’s art:

This is “Women’s Dance” (1932), one of a number at parsonart.com showing again Brett’s glorious use of colour.

And for her sense of design:

Bareback Riders [1955; c/o Sothebys]

That DH Lawrence, who died in 1930, was such an influence on her life – the invitation to New Mexico was a complete liberation – is recalled in a 1958 painting:

called “My Three Fates” [Albuquerque Museum], it shows Mabel (left), Frieda (centre) and Brett (right) apparently remembering Lawrence who we see through the doorway sitting writing under a tree, as was his habit.

***